THE belief that God is one substance, yet three persons, is one of

the central doctrines of the Christian religion. The concept of the

Trinity is believed by most professing Christians, whether Catholic

or Protestant.

A Gallup Poll taken in 1966 found that 97% of the American public

believed in God. Of that number, 83% believed that God is a

Trinity.

Yet for all this belief in the Trinity, it is a doctrine that is not

clearly understood by most Christian laymen. In fact, most have

neither the desire nor the incentive to understand what their church

teaches. Few laymen are aware of any problems with the doctrine of

the Trinity. They simply take it for granted — leaving the

mysterious doctrinal aspects to theologians.

And if the layman were to investigate further, he would be confronted

with discouraging statements similar to the following: “The mind

of man cannot fully understand the mystery of the Trinity. He who

would try to understand the mystery fully will lose his mind. But he

who would deny the Trinity will lose his soul” (Harold Lindsell

and Charles J. Woodbridge, A Handbook of Christian Truth, pp.

51-52).

Such a statement means that the concept of the Trinity should be

accepted or else. But, merely to accept it as doctrine without

proving it would be totally contrary to Scripture. God inspired Paul

to write: “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good”

(I Thes. 5:21).

Peter further admonished Christians: “. . . Be ready always to

give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that

is in you.. .“ (I Peter 3:15).

Therefore the Christian is duty bound to prove whether or not God is

a Trinity.

If you were to confine yourself to reading the articles on the

Trinity in popular religious literature for laymen, you would

conclude that the Trinity is everywhere and clearly taught in the

Bible. However, if you were to begin to read what the more technical

Bible encyclopedias, dictionaries and books say on the subject, you

would come to an entirely different conclusion. And the more you

studied, the more you would find that the Trinity is built on a very

shaky foundation indeed.

The problems inherent in clearly explaining the Trinity are expressed

in nearly every technical article or book on the subject.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia begins: “It is difficult, in the

second half of the 20th century, to offer a clear, objective, and

straightforward account of the revelation, doctrinal evolution, and

the theological elaboration of the mystery of the Trinity.

Trinitarian discussion, Roman Catholic as well as other, presents a

somewhat unsteady silhouette” (Vol. XIV, p. 295). (Emphasis ours

throughout booklet.)

But why should the central doctrine of the Christian faith be so

difficult to understand? Why should such an important doctrine

present an unsteady silhouette? Isn't there a clear biblical

revelation of the doctrine of the Trinity? Didn't Christ and the

apostles plainly teach it?

Surely the Bible would be filled with teachings about such an

important subject as the Trinity. But, unfortunately the word

“Trinity” never appears in the Bible.

‘The term ‘Trinity’ is not a Biblical term, and we are

not using Biblical language when we define what is expressed by it as

the doctrine” (The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia,

article “Trinity,” p. 3012).

Not only is the word “Trinity” never found in the Bible,

there is no substantive proof such a doctrine is even indicated.

In a recent book on the Trinity, Catholic theologian Karl Rahner

recognizes that theologians in the past have been “. . .

embarrassed by the simple fact that in reality the Scriptures do not

explicitly present a doctrine of the ‘imminent’ Trinity

(even in John's prologue is no such doctrine)” (The Trinity, p.

22). (Author's emphasis.)

Other theologians also recognize the fact that the first chapter of

John's Gospel — the prologue — clearly shows the

pre-existence and divinity of Christ and does not teach the doctrine

of the Trinity. After discussing John's prologue, Dr. William Newton

Clarke writes: “There is no Trinity in this; but there is a

distinction in the Godhead, a duality in God. This distinction or

duality is used as basis for the idea of an only-begotten Son, and as

key to the possibility of an incarnation” (Outline of Christian

Theology, p. 167).

The first chapter of John's Gospel clearly shows the pre-existence of

Christ. It also illustrates the duality of God. And as Dr. Clarke

points out, the key to the possibility of the incarnation — the

fact that God could become man.

The Apostle John makes plain the unmistakable fact that Jesus Christ

is God (John 1:1-4). Yet we find no Trinity discussed in this

chapter.

Probably the most notorious scripture used in times past as

“proof” of a Trinity is I John 5:7. However, many

theologians recognize that this scripture was added to the New

Testament manuscripts probably as late as the eighth century A.D.

Notice what Jamieson, Fausset and Brown wrote in their commentary:

“The only Greek MSS. [manuscripts], in any form which

support the words, ‘in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the

Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear

witness in earth.. .‘ are the Montfortianus of Dublin, copied

evidently from the modern Latin Vulgate; the Ravianus copied from the

Complutensian Polyglot; a MS. [manuscript] at Naples, with

the words added in the margin by a recent hand; Ottobonianus, 298, of

the fifteenth century, the Greek of which is a mere translation of

the accompanying Latin. All old versions omit the words.”

The conclusions arrived at in their commentary, written over 100

years ago, are still valid today. More conservatively oriented The

New Bible Commentary (Revised) agrees, though “quietly”

with Jamieson, Fausset and Brown. “. . . The words are clearly a

gloss and are rightly excluded by RSV [Revised Standard

Version] even from its margin” (p. 1269).

The editors of Peake’s Commentary on the Bible wax more eloquent

in their belief that the words are not part of the original text.

“The famous interpolation after ‘three witnesses’ is

not printed even in RSV, and rightly. It cites the heavenly testimony

of the Father, the logos, and the Holy Spirit, but is never used in

the early Trinitarian controversies. No respectable Greek MS contains

it. Appearing first in a late 4th century Latin text, it entered the

Vulgate and finally the NT [New Testament] of Erasmus”

(p. 1038).

Scholars clearly recognize that I John 5:7 is not part of the New

Testament text. Yet it is still included by some fundamentalists as

biblical proof for the Trinity doctrine.

Even the majority of the more recent New Testament translations do

not contain the above words. They are not found in Moffatt, Phillips,

the Revised Standard Version, Williams, or The Living Bible (a

paraphrase).

It is clear, then, that these words are not part of the inspired

canon, but rather were added by a “recent hand.” The two

verses in I John should read: “For there are three that bear

record, the Spirit, and the water and the blood: and these three

agree in one.”

Three things bear record. But what do they bear record to? A Trinity?

We shall see.

The Spirit, the water and the blood bear record of the fact that

Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is living His life over again in us.

John clarifies it in verses 11-12:

“And this is the record, that God hath given to us eternal life,

and this life is in his Son. He that hath the Son hath life; and he

that hath not the Son of God hath not life.”

But how do these three elements — the Spirit, the water, and the

blood — specifically bear witness to this basic biblical

truth?

“The Spirit beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the

children of God” (Rom. 8:16). (We will see more about the part

the Spirit plays in Chapter Three.)

Water is representative of baptism, which bears witness of the burial

of the old self and the beginning of a new life (Rom. 6:1-6).

The blood represents Christ's death by crucifixion, which pays the

penalty for our sins, reconciling us to God (Rom. 5:9, 10).

Now understand why Christ commanded the apostles to baptize in the

name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19). First

of all, Jesus did not command the apostles to baptize in the name of

the Father, the Son and the Spirit as an indication that God is a

Trinity. No such relationship is indicated in the Bible.

Why, then, were they to baptize using these three names? The answer

is clear.

They were to baptize in the name of the Father because it is the

goodness of God that brings us to repentance (Rom. 2:4), and because

the Father is the One “of whom the whole family in heaven and

earth is named” (Eph. 3:15). In the name of the Son because He

is the one who died for our sins, and in the name of the Spirit

because God sends His Spirit, making us His begotten Sons (Rom.

8:16).

Many theologians have misunderstood the part that the Father, the Son

and the Holy Spirit play in each person’s salvation. The

doctrine of the Trinity is the result of that misunderstanding.

The Trinity is not a biblical doctrine. It has no basis in biblical

fact. Then how did this doctrine come to be believed by the

Church?

The ancient idea of monotheism was shattered by the sudden

appearance of Jesus Christ on the earth. Here was someone who claimed

He was the Son of God. But how could He be? The Jewish people

believed for centuries that there was only one God. If the claims of

“this Jesus” were accepted, then in their minds their

belief would be no different from that of the polytheistic pagans

around them. If He were the Son of God, their whole system of

monotheism would disintegrate.

When Jesus plainly told certain Jews of His day that He was the Son

of God, some were ready to stone Him for blasphemy (John 10:33).

To get around the problem of a plurality in the Godhead, the Jewish

community simply rejected Jesus. And to this day, Orthodox Jews will

not accept Jesus’ Messiahship. However, the more liberal Jews

will at least admit that He was a great man — maybe even a

prophet.

But the “new” Christian religion was still faced with the

problem. How would proponents explain that there was only one God,

not two?

“The determining impulse to the formulation of the doctrine of

the Trinity in the church was the church's profound conviction of the

absolute Deity of Christ, on which - as on a pivot - the whole

Christian concept of God from the first origin of Christianity

turned” (International Standard Biblical Encyclopedia, article

“Trinity,” p. 3021).

But the Deity of Christ does not mean that a doctrine of the Trinity

is necessary, as we shall see in Chapter Two.

Many of the early church fathers were thoroughly educated in Greek

philosophy, from which they borrowed such non-biblical concepts as

dualism and the immortality of the soul. However, most theologians,

for obvious reasons, are generally careful to point out that they did

not borrow the idea of the Trinity from the Triads of Greek

philosophy or those of the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians.

But some are not so careful to make such a distinction.

“Although the notion of a Triad or Trinity is characteristic of

the Christian religion, it is by no means peculiar to it. In Indian

religion, e.g., we meet with the Trinitarian group of Brahma, Siva,

and Visnu; and the Egyptian religion with the Trinitarian group of

Osiris, Isis, and Horus, constituting a divine family, like the

Father, Mother and Son in medieval Christian pictures. Nor is it only

in historical religions that we find God viewed as a Trinity. One

recalls in particular the Neo-Platonic view of the Supreme or

Ultimate Reality, which was suggested by Plato . . .“

(Hasting’s Bible Dictionary, Vol. 12, p. 458).

Of course, the fact that someone else had a Trinity does not in

itself mean that the Christians borrowed it. McClintock and Strong

make the connection a little clearer.

“Toward the end of the 1st century, and during the 2nd, many

learned men came over both from Judaism and paganism to Christianity.

These brought with them into the Christian schools of theology their

Platonic ideas and phraseology” (article “Trinity,”

Vol. 10, p. 553).

In his book, A History of Christian Thought, Arthur Cushman McGiffert

points out that the main argument against those who believed that

there was only one God and that Christ was either an adopted or a

created being was that their idea did not agree with Platonic

philosophy. Such teachings were “offensive to theologians,

particularly to those who felt the influence of the Platonic

philosophy” (ibid., p. 240).

In the latter half of the third century, Paul of Samosata tried to

revive the adoptionist idea that Jesus was a mere man until the

Spirit of God came upon Him at baptism making him the Anointed One,

or Christ. In his beliefs about the person of Jesus Christ, he

“rejected the Platonic realism which underlay most of the

Christological speculation of the day” (ibid., p. 243).

At the end of his chapter on the Trinity, McGiffert concludes:

“. - . It has been the boast of orthodox theologians that in the

doctrine of the Trinity both religion and philosophy come to highest

expression” (Vol. I, p. 247).

The influence of Platonic philosophy on the Trinity doctrine can

hardly be denied.

However, Trinitarian ideas go much further back than Plato.

“Though it is usual to speak of the Semitic tribes as

monotheistic; yet it is an undoubted fact that more or less all over

the world the deities are in triads. This rule applies to eastern and

western hemispheres, to north and south. Further, it is observed

that, in some mystical way, the triad of three persons is one.... The

definition of Athanasius [a fourth-century Christian] who

lived in Egypt, applied to the trinities of all heathen

religions” (Egyptian Belief and Modern Thought, by James

Bonwick, F.R.G.S., p. 396).

It was Athanasius’ formulation for the Trinity which was adopted

by the Catholic Church at the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325.

Athanasius was an Egyptian from Alexandria and his philosophy was

also deeply rooted in Platonism.

“The Alexandrian catechetical school, which revered Clement of

Alexandria and Origen, the greatest theologians of the Greek Church,

as its heads, applied the allegorical method to the explanation of

Scripture. Its thought was influenced by Plato: its strong point was

theological speculation. Athanasius and the three Cappadocians had

been included among its members. . .“ (Ecumenical Councils of

the Catholic Church, by Hubert Jedin, p. 29).

In order to explain the relationship of Christ to God the Father, the

church fathers felt that it was necessary to use the philosophy of

the day. They obviously thought that their religion would be more

palatable if they made it sound like the pagan philosophy that was

extant at the time. These men were versed in philosophy, and that

philosophy colored their understanding of the Bible.

It was the doctrine of the Trinity — colored by the philosophy

of the time — that was accepted by the Church in the early part

of the fourth century — over three hundred years after Christ's

death.

Even theologians recognize that the Trinity is a creation of the

fourth century, not the first!

“There is recognition on the part of exegetist and Biblical

theologians, including a constantly growing number of Roman

Catholics, that one should not speak of Trinitarianism in the New

Testament without serious qualification. There is also the closely

parallel recognition— that when one does speak of unqualified

Trinitarianism, one has moved from the period of Christian origins to

say, the last quadrant of the 4th century. It was only then that what

might be called the definitive Trinitarian dogma ‘one God in

three persons’ became thoroughly assimilated into Christian life

and thought” (New Catholic Encyclopedia, article

“Trinity,” Vol. 14, p. 295).

It was at the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 that two members of

the Alexandrian congregation, Anus, a priest, who believed that

Christ was not a God, but a created being; and Athanasius, a deacon

who believed that the Father, Son and Spirit are the same being

living in a threefold form (or in three relationships, as a man may

be at the same time a father, a son and a brother), presented their

cases.

The Council of Nicaea was not called by the church leaders, as one

might suppose. It was called by the Emperor Constantine. And he had a

far-from-spiritual reason for wanting to solve the dispute that had

arisen.

“In 325 the Emperor Constantine called an ecclesiastical council

to meet at Nicaea in Bithynia. In the hope of securing for his throne

the support of the growing body of Christians he had shown them

considerable favor and it was to his interest to have the church

vigorous and united. The Arian controversy was threatening its unity

and menacing its strength. He therefore undertook to put an end to

the trouble. It was suggested to him, perhaps by the Spanish bishop

Hosius who was influential at court, that if a synod were to meet

representing the whole church both east and west, it might be

possible to restore harmony. Constantine himself of course neither

knew or cared anything about the matter in dispute but he was eager

to bring the controversy to a close, and Hosius’ advice appealed

to him as sound” (A History of Christian Thought, Vol. I, p.

258).

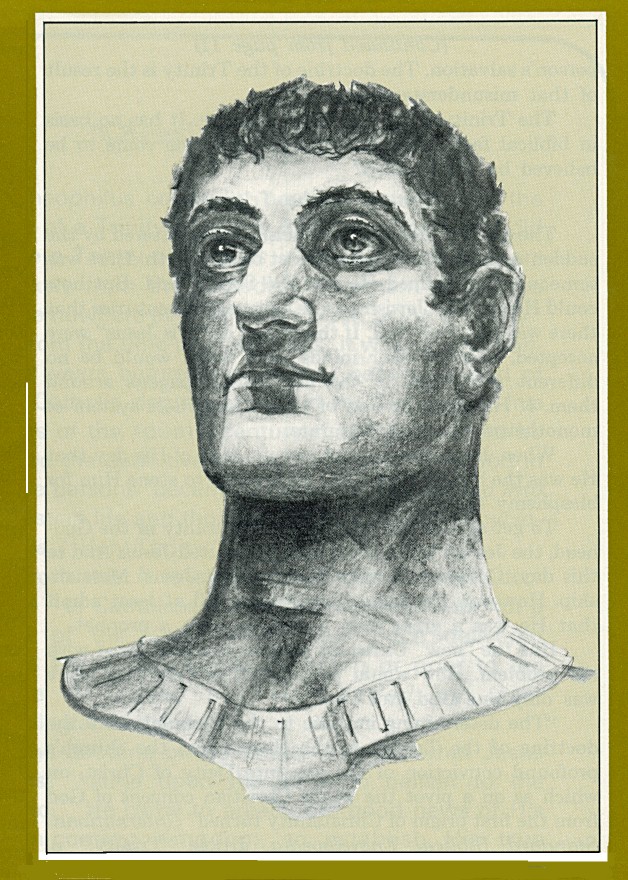

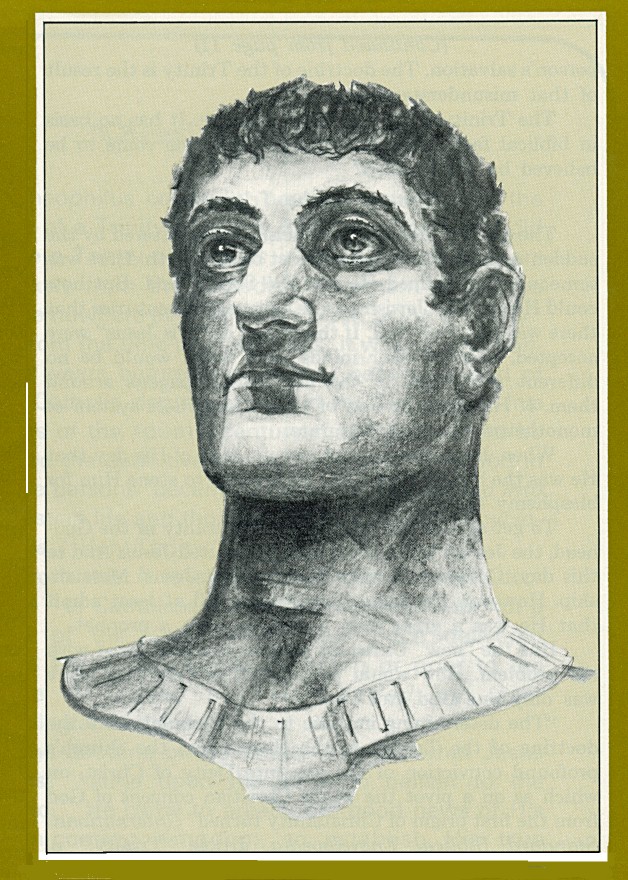

EMPEROR CONSTANTINE convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. in an attempt to restore harmony and unity to a church divided by the Arian controversy. Ambassador College Art

The decision as to which of the two men the church was to follow was

a more or less arbitrary one. Constantine really didn't care which

choice was made — all he wanted was a united church. (Anus was

banished, but later recalled by Constantine, examined and found to be

without heresy.)

The majority of those present at the council were not ready to take

either side in the controversy. “A clearly defined standpoint

with regard to this problem — the relationship of Christ to God

— was held only by the attenuated group of Arians and a far from

numerous section of delegates, who adhered with unshaken conviction

to the Alexandrian [Athanasius’] view. The bulk of the

members occupied a position between these two extremes. They rejected

the formulae of Anus, and declined to accept those of his opponents..

. the voting was no criterion of the inward conviction of the

council” (Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., article

“Nicaea, Council of,” p. 641).

The council rejected Anus’ views, and rightly so, but they had

nothing with which to replace it. Thus the ideas of Athanasius —

also a minority view — prevailed. The rejection of Arianism was

not blanket acceptance of Athanasius. Yet, the church in all the

ensuing centuries has been “stuck,” so to speak, with the

job of upholding — right or wrong — the decision made at

Nicaea.

After the council the Trinity became official dogma in the church,

but the controversy did not end. In the next few years more

Christians were killed by other Christians over that doctrine than

were killed by all the pagan emperors of Rome. Yet, for all the

fighting and killing, neither of the two parties had a biblical leg

to stand on.