Sometime ago I heard of an old man down on a hill farm in the South, who sat on his front porch as a newcomer to the neighborhood passed by. The newcomer to make talk said, "Mister, how does the land lie around here'" The old man replied, "Well, I don't know about the land a-lying; it's these real estate people that do the lying."

In a very real sense the land does not lie; it bears a record of what men write on it. In a larger sense a nation writes its record on the land, and a civilization writes its record on the land - a record that is easy to read by those who understand the simple language of the land.

Let us read together some of the records that have been written on the land in the westward course of civilization from the Holy Lands of the Near East to the Pacific coast of our own country through a period of some 7,000 years.

Records of mankind's struggles through the ages to find a lasting adjustment to the land are found written across the landscapes as "westward the course of empire took its way." Failures are more numerous than successes, as told by ruins and wrecks of works along this amazing trail. From these failures and successes we may learn much of profit and benefit to this young Nation of the United States as it occupies a new and bountiful continent and begins to set up house for a thousand or ten thousand years - yea, for a boundless future.

Conquest of the Land Through 7000 Years

Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 99

U. S. Department of Agriculture

Soil Conservation Service

In 1938 and 1939, Dr. Lowdermilk, formerly Assistant Chief of Soil Conservation Service, made an 18-month tour of western Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East to study soil erosion and land use in those areas. This tour was sponsored by the Soil Conservation Service at the request of a congressional committee.

The main objective of the tour was to gain information from those areas - where some lands had been in cultivation for hundreds and thousands of years - that might be of value in helping to solve the soil erosion and land use problems of the United States.

During the 1938-39 tour, Dr. Lowdermilk visited England, Holland, France, Italy, Algeria, Tunisia, Tripoli, Egypt, Palestine, Trans-Jordan, Lebanon, Cyprus, Syria, and Iraq. Before that time, he had spent several years in China where he had studied soil erosion and land use problems.

After his return to this country, Dr. Lowdermilk gave numerous lectures, illustrated with lantern slides, about his findings on land use in the Old World. "Conquest of the Land Through Seven Thousand Years," issued in mimeograph form in 1942, was the essence of those lectures. It was used extensively in conjunction with lantern slides by school teachers and other lecturers. The lecture notes with some additional information have now been made into this illustrated booklet.

Most of the illustrations used were made from photographs taken by Dr. Lowdermilk during his travels.

Pearl Harbor, like an earthquake, shocked the American people to a realization that we are living in a dangerous world - dangerous for our way of life and for our survival as a people, and perilous for the hope of the ages in a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Why should the world be dangerous for such a philanthropic country as ours?

The world is made dangerous by the desperation of peoples suffering from privations and fear of privations, brought on by restrictions of the exchange of the good and necessary things of Mother Earth. Industrialization has wrought in the past century far reaching changes in civilization, such as will go on and on into our unknown future.

Raw materials for modern industry are localized here and there over the globe. They are not equally available to national groups of peoples who have learned to make and use machines.

Wants and needs of food and raw materials have been growing up unevenly and bringing on stresses and strains in international relations that are seized upon by ambitious peoples and leaders to control by force the sources of such food and raw materials. Wars of aggression, long and well-planned, take place so that such materials can be obtained.

These conflicts are not settled for good by war. The problems are pushed aside for a time only to come back in more terrifying proportions at some later time. Lasting solutions will come in another way. We can depend on the reluctance of peoples to launch themselves into war, for they go to war because they fear something worse than war, either real or propagandized.

A just relation of peoples to the earth rests not on exploitation, but rather on conservation - not on the dissipation of resources, but rather on restoration of the productive powers of the land and on access to food and raw materials. If civilization is to avoid a long decline, like the one that has blighted North Africa and the Near East for 13 centuries, society must be born again out of an economy of exploitation into an economy of conservation.

We are now getting down to fundamentals in this relationship of a people to the land. My experience with famines in China taught me that in the last reckoning all things are purchased with food. This is a hard saying; but the recent world-wide war shows up the terrific reach of this fateful and awful truth.

Aggressor nations used the rationing of food to subjugate rebellious peoples of occupied countries. For even you and I will sell our liberty and more for food, when driven to this tragic choice. There is no substitute for food.

Seeing what we will give up for food, let us look at what food will buy - for money is merely a symbol, a convenience in the exchange of the goods and services that we need and want. Food buys our division of labor that begets our civilization.

Not until tillers of soil grew more food than they themselves required were their fellows released to do other tasks than the growing of food - that is, to take part in a division of labor that became more complex with the advance of civilization.

True, we have need of clothing, of shelter, and of other goods and services made possible by a complex division of labor, founded on this food production, when suitable raw materials are at hand.

And of these the genius of the American people has given us more than any other nation ever possessed. They comprise our American standard of living. But these other good things matter little to hungry people as I have seen in the terrible scourges of famine.

Food comes from the earth. The land with its waters gives us nourishment. The earth rewards richly the knowing and diligent but punishes inexorably the ignorant and slothful. This partnership of land and farmer is the rock foundation of our complex social structure.

In 1938, in the interests of a permanent agriculture and of the conservation of our land resources, the Department of Agriculture asked me to make a survey of land use in olden countries for the benefit of our farmers and stockmen and other agriculturists in this country. This survey took us through England, Holland, France, Italy, North Africa, and the Near East. After 18 months it was interrupted by the outbreak of war when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. We were prevented from continuing the survey through Turkey, the Balkan States, southern Germany, and Switzerland as was originally planned. But in a year and a half in the olden lands we discovered many things of wide interest to the people of America.

We shall begin our reading of the record as it is written on the land in the Near East. Here, civilization arose out of the mysteries of the stone age and gave rise to cultures that moved eastward to China and westward through Europe and across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas.

We are daily and hourly reminded of our debt to the Sumerian peoples of Mesopotamia whenever we use the wheel that they invented more than 6,000 years ago. We do homage to their mathematics each time we look at the clock or our watches to tell time divided into units of 60.

Moreover, our calendar in use today is a revision of the method the ancient Egyptians used in dividing the year. We inherit the experience and knowledge of the past more than we know.

Agriculture had its beginning at least 7,000 years ago and developed in two great centers - the fertile alluvial plains of Mesopotamia and the Valley of the Nile. We shall leave the interesting question of the precise area in which agriculture originated to the archaeologists. It is enough for us to know that it was in these alluvial plains in an arid climate that tillers of soil began to grow food crops by irrigation in quantities greater than their own needs. This released their fellows for a division of labor that gave rise to what we call civilization. We shall follow the vicissitudes of peoples recorded on the land, as nations rose and fell in these fateful lands.

A survey of such an extensive area in the short time of 2 years called for simple but fundamental methods of field study. With the aid of agricultural officials of other countries, we hunted out fields that had been cultivated for a thousand years - the basis of a permanent agriculture. Likewise, we tried to find the reasons why lands formerly cultivated had been wasted or destroyed, as a warning to our farmers and our city folks of a possible similar catastrophe in this new land of America. A simplified method of field study enabled us to examine large areas rapidly.

In the Zagros Mountains that separate Persia from Mesopotamia, shepherds with their flocks have lived from time immemorial, when "the memory of man runneth not to the contrary." From time to time they have swept down into the plain to bring devastation and destruction upon farming and city peoples of the plains. Such was the beginning of the Cain and Abel struggle between the shepherd and the farmer, of which we shall have more to say.

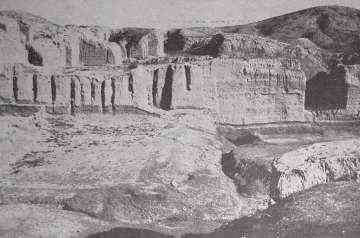

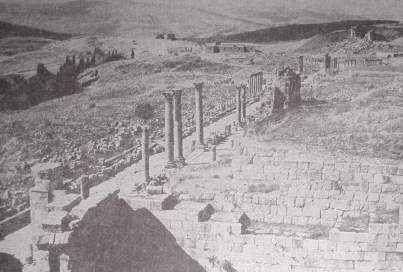

At Kish, we looked upon the first capital after the Great Flood that swept over Mesopotamia in prehistoric times and left its record in a thick deposit of brown alluvium. The layer of alluvium marked a break in the sequence of a former and a succeeding culture, as recorded in artifacts. Above the alluvium deposits is the site of Kish (fig. 1).

[Figure l. Ruins of Kish, one of the world's most important cities 6,000 years ago. Recently, archaeologists excavated these ruins from beneath the desert sands of Mesopotamia.]

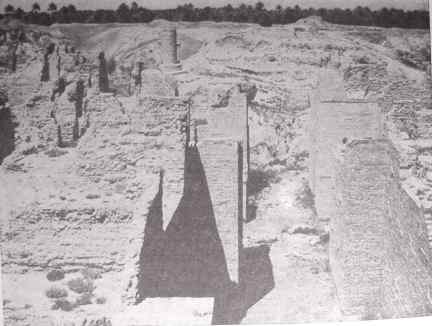

At the ruins of mighty Babylon we pondered the ruins of Nebuchadnezzar's stables (fig. 2), adorned by animal figures in bas-relief. We stood subdued as though at a funeral as we recalled how this great ruler of Babylon had boasted:

"That which no king before had done, I did ...A wall like a mountain that cannot be moved, I builded ... great canals I dug and lined them with burnt brick laid in bitumen and brought abundant waters to all the people ...I paved the streets of Babylon with stone from the mountains ...magnificent palaces and temples I have built ... Huge cedars from Mount Lebanon I cut down ...with radiant gold I overlaid them and with jewels I adorned them."

[FIGURE 2. Ruins of the famous stables of Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon built during the sixth century B. C. Babylon died and was buried by the desert sands, not because it was sacked and razed but because the irrigation canals that watered the land that supported the city were permitted to fill with silt.]

Then came to mind the warnings of the Hebrew prophets that were thundered against the wicked city. They warned that Babylon would become

"A desolation... a dry land and a wilderness, a land wherein no man dwelleth... And wolves shall cry in their castles, and jackals in the pleasant places" (Jer 51:29,37,43; Isa 13:22).

Believe it or not, the only living thing that we saw in this desolation that once was Babylon was a lean gray wolf, shaking his head as if he might have a tick in his ear, as he loped to his lair in the ruins of one of the seven wonders of the ancient world - the Hanging Gardens of Babylon where air conditioning was in use 2,600 years ago.

Mesopotamia, the traditional site of the Garden of Eden, out of which come the stories of the Flood, of Noah and the Ark, of the "Tower of Babel" and the confusion of tongues, of the fiery furnace which we found still burning today, is jotted full of records of a glorious past, of dense populations, and of great cities that are now ruins and desolation. For at least 11 empires have risen and fallen in this tragic land in 7,000 years. It is a story of a precarious agriculture practiced by people who lived and grew up under the threat of raids and invasions from the denizens of grasslands and the desert, and of the failure of their irrigation canals because of silt.

Agriculture was practiced in a very dry climate by canal irrigation with muddy water from the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. This muddy water was the undoing of empire after empire. As muddy river waters slowed down, they choked up the canals with silt. It was necessary to keep this silt out of the canals year after year to supply life-giving waters to farm lands and to cities of the plain.

As Populations grew, canals were dug farther and farther from the rivers. This great system of canals called for a great force of hand labor to keep them clean of silt. The rulers of Babylon brought in war captives for this task. Now we understand why the captive Israelites "sat down by the waters of Babylon and wept" (Psa 137:1). They also were, doubtless, required to dig silt out of canals of Mesopotamia.

As these great public works of cleaning silt out of canals were interrupted from time to time by internal revolutions and by foreign invaders, the peoples of Mesopotamia were brought face to face with disaster in canals choked with silt. Stoppage of canals by silt depopulated villages and cities more effectively than the slaughter of people by an invading army.

On the basis of an estimate that it was possible in times past to irrigate 21,000 of the 35,000 square miles of the alluvium of Mesopotamia, the population of Mesopotamia at its zenith was probably between 17 and 25 million. The present population of all Iraq is estimated to be about 4 million, including nomadic peoples. Of this total, not more than 3 1/2 million live on the alluvial plain.

Decline in population in Mesopotamia is not due to loss of soil by erosion. The fertile lands are still in place and lifegiving waters still flow in the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, ready to be spread upon the lands today as in times past. Mesopotamia is capable of supporting as great a population as it ever did and greater when modern engineering makes use of reinforced concrete construction for irrigation works and powered machinery to keep canal systems open.

A greater area of Mesopotamia thus might be farmed than ever before in the long history of this tragic land. But erosion in the hinterlands aggravated the silt problem in waters of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, as they were drawn off into the ancient canal systems. Invasions of nomads out of the grasslands and the desert brought about the breakdown of irrigation that spelled disaster after disaster.

Let's now turn to the other great center of population growth and development of civilization in the Valley of the Nile. Here, the mysterious Sphinx ponders problems of the ages as he looks out over the narrow green Valley of the Nile, lying across a brown and sun-scorched desert.

In Egypt as well as in Mesopotamia, tillers of soil learned early to sow food plants of wheat and barley and to grow surplus food that released their fellows for divisions of labor, giving rise to the remarkable civilization that arose in the Valley of the Nile. Our debt to the ancient Egyptians is great.

Here, too, farming grew up by flood irrigation with muddy waters. But the problems of farming were very different from those of Mesopotamia. Annual flooding with silt-laden waters spread thin layers of silt over the land, raising it higher and higher. In these flat lands of slowly accumulating soil, farmers never met with problems of soil erosion.

To be sure, there have been problems of salt accumulation and of rising water tables for which drainage is the solution. This is especially true since yearlong irrigation has been made possible by the Assuan Dam. But the body of the soil has remained suitable for cropping for 6,000 years and more.

It was perhaps in the Valley of the Nile that a genius of a farmer about 6,000 years ago hitched an ox to a hoe and invented the plow, thus originating power-farming to disturb the social structure of those times much as the tractor disturbed the social structure of our country in recent years. By this means farmers became more efficient in growing food; a single farmer released several of his fellows from the vital task of growing food for other tasks. Very likely the Pharaohs had difficulty in keeping this surplus population sufficiently occupied. For we suspect that the Pyramids were the first WPA projects.

We shall follow the route of Moses out of the fertile, irrigated lands of Egypt into a mountainous land where forests and fields were watered with the rain of Heaven. Fields cleared on mountain slopes presented a new problem in farming - the problem of soil erosion, which, as we shall see, became the greatest hazard to Permanent agriculture and an insidious enemy of civilization.

We crossed the modern Suez Canal with its weird color of blue into Sinai where the Israelites with their herds wandered for 40 years. They or someone must have overgrazed the Peninsula of Sinai, for it is now a picture of desolation. We saw in this landscape how the original brown soil mantle was eroded into enormous gullies as shown by great yellowish gashes cut into the brown soil covering. I had not expected to find evidences of so much accelerated erosion in the arid land of Sinai.

On the way to Aqaba we crossed a remarkable landscape, a plateau that had been eroded through the ages almost to a plain, called a peneplain in physiographic language.

This peneplain surface dates back to Miocene times, in the geological scale. In the plain now there is no evidence of accelerated cutting by torrential streams and no evidence that climate has changed for drier or wetter conditions since Miocene times. Here is a cumulative record going far back of the ice age, proclaiming that in this region climate has been remarkably stable.

From this plateau we dropped down 2,500 feet into the Araba or gorge of the great rift valley that includes the Gulf of Aqaba, the Araba, the Dead Sea, and the Valley of the Jordan. At the head of the Gulf of Aqaba of the Red Sea we found Dr. Nelson Glueck excavating Ezion Geber which he calls the ancient Pittsburg of the Red Sea, or Solomon's Seaport. Here, copper was smelted 2,800 years ago to furnish instruments for Solomon and his people. The mud brick used for building these ancient houses looked just like our adobe brick of New Mexico and Arizona.

As we climbed out of the rift valley over the east wall to the plateau of Trans-Jordan that slopes toward the Arabian Desert, we came near Amman upon the same type of peneplain that we crossed west of the Araba. Topographically, these two plains are parts of the same peneplain that once spread unbroken across this region. But toward the end of Pliocene times - that is, just before the beginning of the ice age - a series of parallel faults let down into it the great rift valley to form one of the most spectacular examples of disturbances in the earth's crust that is known to geologists.

From Ma'an we proceeded past an old Roman dam, silted up and later washed out and left isolated as a meaningless wall. At Elji we took horses to visit the fantastic ruins of ancient Petra (called Sela in the Old Testament). This much-discussed city was the capital of the Nabatean civilization and flourished at the same time as the Golden Age of China - 200 B. C. to A. D. 200. Rose-red ruins of a great city are hidden away in a desert gorge on the margin of the Arabian Desert.

Petra is now the desolate ruin of a great center of power and culture. It has been used by some students as evidence that climate has become drier in the past 2,000 years, making it impossible for this land to support as great a population as it did in the past. In contradiction to this conclusion, we found slopes of the surrounding valley covered with terrace walls that had fallen into ruin and allowed the soils to be washed off to bare rock over large areas. These evidences showed that food had been grown locally and that soil erosion had damaged the land beyond use for crops.

Invasion of nomads out of the desert had probably resulted in a breakdown in these measures for the conservation of soil and water. Also, erosion washed away the soils from the slopes and undermined the carrying capacity of this land for a human population. Before ascribing decadence of the region to change of climate, we must know how much the breakdown of intensive agriculture contributed to the fall and disappearance of this Nabatean civilization.

The great buildings used for public purposes are amazing. Temples, administrative buildings, and tombs are all carved out of the red Nubian sandstone cliffs. A fascinating story still lies hidden in the unexcavated ruins of this ancient capital. The influence of Greek and Roman civilization was found in a great theater with a capacity to seat some 2,500 persons. It was carved entirely out of massive sandstone rock that now only echoes the scream of eagles, or the chatter of tourists.

And as we proceeded northward in the Biblical land of Moab, we came to the site of Mt. Nebo. We were reminded of how Moses, after having led the Israelites through 40 years of wandering in the wilderness, stood on this mountain and looked across the Jordan Valley to the Promised Land. He described it to his followers in words like these:

"For the Lord thy God bringeth thee into a good land, a land of brooks of water of fountains and depths that spring out of valleys and hills; a land of wheat and barley and vines and fig trees and pomegranates, a land of olive oil and honey; a land wherein thou shalt eat bread without scarceness; thou shalt not lack anything in it; a land whose stones are iron and out of whose hills thou mayest dig brass" (Deut 8:7-9).

We crossed the Jordan Valley as did Joshua and found the Jordan River a muddy and disappointing stream. We stopped at the ruins of Jericho and dug out kernels of charred grain which the archaeologists tell us undoubtedly belonged to an ancient household of this ill-fated city. We looked at the Promised Land as it is today, 3000 years after Moses described it to the Israelites as a "land flowing with milk and honey."

We found the soils of red earth washed off slopes to bedrock over more than half the upland area. These soils had lodged in the valleys where they are still being cultivated and are still being eroded by great gullies that cut through the alluvium with every heavy rain. Evidence of rocks washed off the hills were found in piles of stone where tillers of soil had heaped them together to make cultivation about them easier.

From the air we read with startling vividness the graphic story as written on the land. Soils had been washed off to bedrock in the vicinity of Hebron and only dregs of the land were left behind in narrow valley floors, still cultivated to meager crops.

In the denuded highlands of Judea are ruins of abandoned village sites. Capt. P. L. O. Guy, director of the British School of Archaeology, has studied in detail those sites found in the drainage of Wadi Musrara that were occupied 1,500 years ago. Since that time they have been depopulated and abandoned in greater numbers on the upper slopes.

Captain Guy divided the drainage of Musrara into 3 altitudinal zones: The plain, 0-325 feet; foothills, 325-975 feet; and mountains, 975 feet and over.

In the plain, 34 sites were occupied and 4 abandoned; in the foothills, 31 occupied and 65 abandoned; and in the mountains, 37 occupied and 124 abandoned. In other words, villages have thus been abandoned in the 3 zones by percentages in the above order of 11, 67, and 77, which agrees well with the removal of soil.

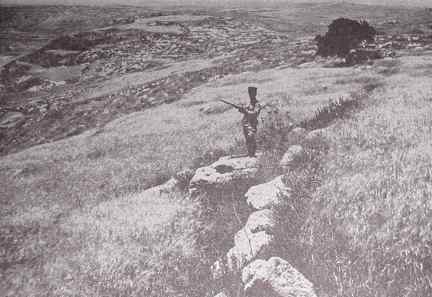

It is little wonder that villages were abandoned in a landscape such as this in the upper zone near Jerusalem. The soil, the source of food supply, has been wasted away by erosion. Only remnants of the land left in drainage channels are held there by cross walls of stone.

[FIGURE 3. This is a present-day view of a part of the Promised Land to which Moses led the Israelites about 1200 B. C. A few patches still have enough soil to raise a meager crop of barley. But most of the land has lost practically all of its soil, as observed from the rock outcroppings. The crude rock terrace in the foreground helps hold some of the remaining soil in place.]

Where soils are held in place by stone terrace walls, that have been maintained down to the present, the soils are still cultivated after several thousand years. They are still producing, but not heavily, to be sure, because of poor soil management (fig. 3).

Most important, the soils are still in place and will grow bigger crops with improved soil treatment. The glaring hills of Judea, not far from Jerusalem, are dotted with only a few of their former villages. Terraces on these hills have been kept in repair for more than 2,000 years.

What is the cause of the decadence of this country that was once flowing with milk and honey? As we ponder the tragic history of the Holy Lands, we are reminded of the struggle of Cain and Abel. This struggle has been made realistic through the ages by the conflict that persists, even unto today, between the tent dweller and the house dweller, between the shepherd and the farmer.

The desert seems to have produced more people than it could feed. From time to time the desert people swept down into the fertile alluvial valleys where, by irrigation, tillers of soil grew abundant foods to support teeming villages and thriving cities.

They swept down as a wolf on the fold to raid the farmers' supplies of food. Raiders sacked and robbed and passed on. Often, they left destruction and carnage in their path, or they replaced former populations and became farmers themselves, only to be swept out by a later wave of hungry denizens of the desert.

Conflicts between the grazing and farming cultures of the Holy Lands have been primarily responsible for the tragic history of this region. Not until these two cultures supplement each other in cooperation can we hope for peace in this ancient land.

We saw the tents of descendants of nomads out of Arabia. In the seventh century they swept in out of the desert to conquer and overrun the farming lands of Palestine. Again in the 12th century nomads drove out the Crusaders. They with their herds of long-eared goats let terrace walls fall in ruin and unleashed the forces of erosion. For nearly 13 centuries erosion has been washing the soils off the slopes into the valleys to make marshes or out to sea.

In recent times a great movement has been under way for the redemption of the Promised Land by Jewish settlers. They have wrought wonders in draining swamps, ridding them of malaria, and planting them to thriving orchards and fields. These settlers have also repaired terraces, reforested desolate and rocky slopes and improved livestock and poultry.

Throughout our survey of the work of the agricultural colonies, I was asked to advise on measures to conserve soil and water. I urged that orchards be planted on the contour and the land bench-terraced by contour plowing. We were shown one orchard where the trees were planted on the contour, the land was bench-terraced, and slopes above the orchard were furrowed on the contour and planted to hardy trees.

By these measures all the rain that had fallen the season before, one of the wettest in many years, had been absorbed by the soil. After this work was done, no runoff occurred to cut gullies down slope and to damage the orchards below. We were told that the man responsible for this had learned these measures at the Institute of Water Economy in Tiflis, Georgia, in Transcaucasia.

We crossed the Jordan again into a region famous in Biblical times for its oaks, wheat fields, and well-nourished herds. We found the ruins of Jerash, one of the 10 cities of the Decapolis, and Jerash the second. Archaeologists tell us that Jerash was once the center of some 250,000 people. But today only a village of 7,000 marks this great center of culture, and the country about it is sparsely populated with seminomads. The ruins of this once-powerful city of Greek and Roman culture are buried to a depth of 13 feet with erosional debris washed from eroding slopes.

We searched out the sources of water that nourished Jerash and found a series of springs protected by masonry built in the Graeco-Roman times. We examined these springs carefully with the archaeologists to discover whether the present water level had changed with respect to the original structures and whether the openings through which the springs gushed were the same as those of ancient times. We found no suggestion that the water level was any lower than it was when the structures were built or that the openings were different. It seems that the water supply had not failed.

When we examined the slopes surrounding Jerash we found the soils washed off to bedrock in spite of rock-walled terraces. The soils washed off the slopes had lodged in the valleys. These valleys were cultivated by the seminomads who lived in black goat-hair tents. In Roman times this area supplied grain to Rome and supported thriving communities and rich villas, ruins of which we found in the vicinity.

In the alluvial plains along the Orontes River, agriculture supports a number of cities, much reduced in population from those of ancient times. Water wheels introduced from Persia during or following the conquests of Alexander the Great (300 B. C.) were numerous along the Orontes. There were hundreds, we were told, in Roman times, but today only 44 remain. They are picturesque old structures both in their appearance and in the groans of the turning wheel as they slowly lift water from the river to the aqueduct to supply water for the city of Hama. These wheels are more than 2,000 years old. But no Part of a wheel is that old, because the parts have been replaced piecemeal many times through the centuries.

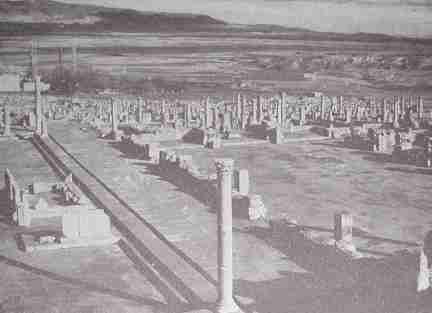

[Figure 4. Ruins of one of the Hundred Dead Cities of Syria. From 3 to 6 feet of soil has been washed off most of the hillsides. This city will remain dead because the land around it can no longer support a city.]

[Figure 4. Ruins of one of the Hundred Dead Cities of Syria. From 3 to 6 feet of soil has been washed off most of the hillsides. This city will remain dead because the land around it can no longer support a city.]

Still farther to the north in Syria, we came upon a region where erosion had done its worst in an area of more than a million acres of rolling limestone country between Hama, Alleppo, and Antioch. French archaeologists, Father Mattern, and others found in this man-made desert more than 100 dead cities.

Butler of Princeton rediscovered this region a generation ago. These were not cities as we know them, but villages and market towns. The ruins of these towns were not buried. They were left as stark skeletons in beautifully cut stone, standing high on bare rock (fig. 4). Here, erosion had done its worst. If the soils had remained, even though the cities were destroyed and the populations dispersed, the area might be repeopled again and the cities rebuilt. But now that the soils are gone, all is gone.

We are told that in A. D. 610-612 a Persian army invaded this thriving region. Less than a generation later, in 633-638, the nomads out of the Arabian Desert completed the destruction of the villages and dispersal of the population. Thus, all the measures for conserving soil and water that had been built up through centuries were allowed to fall into disuse and ruin. Then erosion was unleashed to do its deadly work in making this area a man-made desert.

About 4,500 years ago, we are told by archaeologists, a Semitic tribe swept in out of the desert and occupied the eastern shore of the Mediterranean and established the harbor towns of Tyre and Sidan. On the site of another such ancient harbor town is Beirut, which today is the capital of Lebanon. You can see it from a high point on the Lebanon Mountains overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.

[Figure 5. Rock-walled bench terraces in Lebanon that have been in for thousands of years. The construction of terraces of this type would cost from $2,000 to 5,000 per acre if labor was figured at 40 cents per hour. Such expensive methods of protecting land are practical only where people have no other land on which to raise their food.]

[Figure 5. Rock-walled bench terraces in Lebanon that have been in for thousands of years. The construction of terraces of this type would cost from $2,000 to 5,000 per acre if labor was figured at 40 cents per hour. Such expensive methods of protecting land are practical only where people have no other land on which to raise their food.]

These early Semites were Phoenicians. They found their land a mountainous country with a very narrow coastal plain and little flat land on which to carry out the traditional irrigated agriculture as it had grown up in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

We may believe that as the Phoenician people increased, they were confronted with three choices:

(1) Migration and colonization, which we know they did;

(2) manufacturing and commerce, which we know they did; and

(3) cultivation of slopes, about which we have hitherto heard little.

Here was a land covered with forests and watered by the rains of heaven, a land that held entirely new problems for tillers of soil who were accustomed to the flat alluvial valleys of Mesopotamia and the Nile. As forests were cleared either for domestic use or for commerce, slopes were cultivated. Soils of the slopes eroded then under heavy winter rains as they would now. Here under rain farming, they encountered severe soil erosion and the problem of establishing a permanent agriculture on sloping lands.

We find, as we read the record on the land in this fascinating region, tragedy after tragedy deeply engraved on the sloping land. To control erosion walls were constructed across the slopes. Ruins of these walls can be seen here and there today. These measures failed, and erosion caused the soil to shift down slope. As the fine-textured soil was washed away, leaving loose rocks at the surface, tillers of the soil piled the rocks together to make cultivation about them easier. In these cases the battle with soil erosion was definitely a losing one.

Elsewhere we found that the battle with soil erosion had been won by the construction and maintenance of a remarkable series of rock-walled terraces extending from the bases to the crests of slopes like fantastic staircases (fig. 5). At Belt Eddine in the mountains of Lebanon east of Beirut, we found the slopes terraced even up to grades of 76 percent.

[FIGURE 6. Cedars still grow in Lebanon when given a chance. This is part of one of the four small groves that still exist. It is in the grounds of a monastery and is protected from goat grazing by the stone fence.]

The mountains of ancient Phoenicia were once covered by the famous forests, the cedars of Lebanon. An inscription on the temple of Karnak, as translated by Breasted, announces the arrival in Egypt before 2300 B. C. of 40 ships ladden with timber out of Lebanon.

You will recall that it was King Solomon, nearly 3,000 years ago, who made an agreement with Hiram, King of Tyre, to furnish him cypress and cedars out of these forests for the construction of the temple at Jerusalem. Solomon supplied 80,000 lumberjacks to work in the forest and 70,000 to skid the logs to the sea. It must have been a heavy forest to require such a force. What has become of this famous forest that once covered nearly 2,000 square miles?

Today, only 4 small groves of this famous Lebanon cedar forest are left, the most important of which is the Tripoli grove of trees in the cup of a valley. An examination of the grove revealed some 400 trees of which 43 are old veterans or wolf trees. As we read the story written in tree rings, it appears that about 300 years ago the grove had nearly disappeared with no less than 43 scattered veteran trees standing.

These trees with wide-spreading branches had grown up in an open stand. About that time a little church was built in their midst that made the grove sacred. A stone wall was built about the grove to keep out the goats that grazed over the mountains. Seeds from the veteran trees fell to the ground, germinated, and grew up into a fine close-growing stand of tall straight trees that show how the cedars of Lebanon will make good construction timber when grown in forest conditions (fig. 6).

Such natural restocking also shows that this famous forest has not disappeared because of adverse change of climate, but that under the present climate it would extend itself if it were safe-guarded against the rapacious goats that graze down every accessible living plant on these mountains.

Before moving on to Cyprus and North Africa, let's look at China. Civilization here probably arose somewhat later than that in the Near East and was influenced by it. Mixed agriculture, irrigation, the oxdrawn plow, and terracing of slopes are notable similarities in the two regions (fig. 7).

[FIGURE 7. These bench terraces in Shansi Province illustrate the extent to which some Chinese farmers have gone to conserve the remaining soil on their hillsides.]

It was in China, where I was engaged in an international project for famine prevention in 1922-27, that the full and fateful significance of soil erosion was first burned into my consciousness.

During an agricultural exploration into the regions of North China, seriously affected by the famine of 1920-21. I examined the site where the Yellow River, in 1852, broke from its enormous system of inner and outer dikes. As we traveled across the flat Plains of Honan, we saw a great flat topped hill looming up before us. We traveled on over the elevated plain for 7 miles to another great dike that stretched across the landscape from horizon to horizon. We mounted this dike and there before us lay the Yellow River, the Hwang Ho, a great width of brown water flowing quietly that spring morning into a tawny haze in the east.

Here in a channel fully 40 to 50 feet above the plain of the great delta lay the river known for thousands of years as "China's Sorrow." This gigantic river had been lifted up off the plain over the entire 400-mile course across its delta and had been held in this channel by hand labor of men - without machines or engines, without steel cables or construction timber, and without stone.

Millions of Chinese farmers with bare hands and baskets had built here through thousands of years a stupendous monument to human cooperation and the will to survive. Since the days of Ta-Yu, nearly 4,000 years ago, the battle of floods with this tremendous river have been lost and won time and again.

But why should this battle with the river have to be endless? Any relaxation of vigilance let the river break over its dikes, calling for herculean and cooperative work to put the river back again in its channel. Then suddenly it dawned upon me that the river was brown with silt, heavily laden with soil that was washed out of the highlands of the vast drainage system of the Yellow River.

As its flood waters reached the gentler slope of the delta (1 foot to the mile), the current slowed down and began to drop its load of silt. Deposits of silt in turn lessened the capacity of the channel to carry floodwaters and called on the farmers threatened with angry floods to build up the dikes yet higher and higher, year after year.

There was no end to this demand of the river if it were to be confined between its dikes. Final control of the river so heavily laden with silt was hopeless; yet millions of farmers toiled on.

In 1852, the yellow-brown waters of the Hwang Ho broke out of its elevated channel to seek another way to the sea. It had emptied into the Yellow Sea, where it had usurped the old outlet of the Shai River.

This time the river broke over its dikes near Kaifeng, Honan, and wandered to the northeast over farm lands, destroying villages and smothering the life out of millions of humans, and discharged into the Gulf of Chihli, 400 miles north of its former outlet. In its rage it had refused to be lifted any higher off its plain. Hundreds of thousands of farmers had been defeated. Silt had defeated them, valiant as they were.

Silt--silt--silt! We determined to learn where this silt came from, even up to the headwaters.

In a series of carefully planned agricultural explorations we discovered the source of the silt that brought ruin to millions of farmers in the plains. In the Province of Shansi we found how the line of cultivation was pushed up slopes following the clearing away of forests. Soils, formerly protected by a forest mantle, were thus exposed to summer rains, and soil erosion began a headlong process of destroying land and filling streams with soil waste and detritus.

Without a basis of comparison, we might easily have misread the record as written there on the land. But temple forests, preserved and protected by the Buddhist priests, gave me and my Chinese associates a remarkable chance to measure and compare rates of erosion within these forests and on similar slopes and soils that had been cleared and cultivated.

In brief, my Chinese scientific associates [1 T.I. Li, C. T. Ren, C. O. Lee, and others. See Proceedings of the Pan Pacific Science Congress, Tokyo, 1926.] and I carried out a series of soil-erosion experiments during rainy seasons of 3 years. In these experiments we measured the rate of runoff and erosion by means of runoff plots within temple forests, out on farm fields under cultivation, and on fields abandoned because of erosion. For the first time in soil-erosion studies, we got experimental data for such comparisons. Here too, we found how the Yellow River had become China's Sorrow, for we found that runoff and erosion from cultivated land were many times as great as from temple forests.

It was clear that if the farmers of the delta plain were ever to be safeguarded from the mounting perils of the silt-laden Yellow River, the source of the silt must be stopped by erosion control.

Farther west in the midst of the famous and vast loessial deposits of North China, we found in the Province of Shansi that an irrigation system first established in 246 B.C., had been put out of use by silt. Here again silt was the villain.

[FIGURE 8. These huge gullies indicate the severity of soil erosion in the deep, and once fertile, loessial soils of northern China. Millions of acres have been cut up like this and are now almost worthless.]

[FIGURE 8. These huge gullies indicate the severity of soil erosion in the deep, and once fertile, loessial soils of northern China. Millions of acres have been cut up like this and are now almost worthless.]

We sought out the origin of the silt that had brought an end to an irrigation project that had fed the sons of Han during the Golden Age of China. This origin was found in areas where soil erosion had eaten out gullies 600 feet deep (fig. 8). It was while contemplating such scenes that I resolved to challenge the conclusions of the great German geologist, Baron Von Richthofen, and of Ellsworth Huntington that the decadence of North China was due its desiccation or pulsations of the climate.

Temple forests gave the clue. They demonstrated beyond a doubt that the present climate would support a generous growth of vegetation capable of preventing erosion on such a scale. Human occupation of the land had set in motion processes of soil wastage that were in themselves sufficient to account for the decadence and decline of this part of China, without adverse change of climate.

It was in the presence of such tragic scenes on a gigantic scale that I resolved to run down the nature of soil erosion and to devote my lifetime to study of ways to conserve the lands on which mankind depends.

Let's now go back and follow the westward course of civilization from the Holy Lands through North Africa and on into Europe. In Cyprus we found the land use problems of the Mediterranean epitomized in a comparatively small area.

In the plain of Mesaoria is a telling record in and about a Byzantine church. The church on the outskirts of the village of Asha in eastern Cyprus is surrounded by a graveyard and its wall. The alluvial plain now stands 8 feet above the level of the churchyard as we measured it. On entering the church we stepped down 3 feet from the yard level to the floor of the church. Inside we noted that low pointed arches were blocked off, and new arches had been cut for doors and windows.

The aged vestryman told us that about 30 years ago a flood from the plain had filled the church with water and left 2 feet of silt on the floor. Rather than clean it out, a new stone floor had been laid over the silt deposit. Thus, 8 plus 3 plus 2 equals 13 feet, the height of the present alluvial plain above the original church floor. From these measurements we concluded that the plain had filled in, not less than 13 feet, with erosional debris washed off the drainage slopes.

Along the northern coast of Africa into Tunisia and Algeria we read the record of the granary of Rome during the empire - by surveying a cross section from the Mediterranean to the Sahara Desert, from 40 inches of rainfall to 4 inches, from Carthage on the coast to Biskra at the edge of mysterious Sahara.

In Tunisia we found that it rains in the desert of North Africa in wintertime now as it did in the time of Caesar - in 44 B. C. Caesar complained of how a great rainstorm with wind had blown over the tents of his army encampment and flooded the camp. It rained hard enough to Produce flash floods in the wadies. At one place muddy water swept across the highway in such volume that we decided to wait for the flash flow to go down before proceeding.

We stood on the site of ancient Carthage, the principal city of North Africa in Phoenician and Roman times - the city that produced Hannibal and became a dangerous rival of Rome. In 148 B. C., at the end of the Third Punic War, Scipio destroyed Carthage, but out of the doomed city he saved 28 volumes of a work on agriculture written by a Carthaginian by the name of Mago.

Mago was recognized by the Greeks and Romans as the foremost authority on agriculture in the Mediterranean area. These works of Mago on agricultural subjects were translated by such Roman writers as Columella, Varro, and Cato. The translations tell us that the traditions of conserving soil and water discovered on the slopes of ancient Phoenicia had been brought there by colonists. We suspect these measures furnished the basis of the great agricultural production that was so important to the Romans during the Empire.

Over a large part of the ancient granary of Rome we found the soil washed off to bedrock and the hills seriously gullied as a result of overgrazing. Most valley floors are still cultivated but are eroding in great gullies fed by accelerated storm runoff from barren slopes. This is in an area that supported many great cities in Roman times.

We found at Djemila the ghosts of Cuicul, a city that once was great and populous and rich but later was covered completely, except for about 3 feet of a single column, by erosion debris washed off the slopes of surrounding hills. For 20 years French archaeologists had been excavating this remarkable Roman City and had unearthed great temples, two great forums, splendid Christian churches, and great warehouses for wheat and olive oil. All this had been buried by erosional debris washed from the eroding slopes above the city. The surrounding slopes, once covered with olive groves, are now cut up with active gullies.

The modern village houses only a few inhabitants. The flat lands are still farmed to grain but the slopes are bare and eroding and wasting away. What is the reason for this astounding decline and ruin?

[FIGURE 9. The ruins of Timgad - an ancient Roman city built during the first century A. D. The few huts seen in the center background now house about 300 inhabitants, which is all the eroded land will support. Note that the eroded hills in the background are almost as desolate as the ruins of the city.]

Farther to the south we stopped to study the ruins of another great Roman city of North Africa, Thamugadi, now called Timgad (fig. 9). This city was founded by Trajan in the first century A. D. It was laid out in symmetrical Pattern and adorned with magnificant buildings, with a forum embellished by statuary and carved porticoes, a public library, a theater to seat some 2,500 persons, 17 great Roman baths, and marble flush toilets for the public.

After the invasion of the nomads in the seventh century had completed the destruction of the city and dispersal of its population, this great center of Roman culture and power was lost to knowledge for 1,200 years. It was buried by the dust of wind erosion from surrounding farm lands until only a portion of Hadrian's arch and 3 columns remained like tombstones above the undulating mounds to indicate that once a great city was there.

The French Government has been excavating this great center for 30 years. Remarkable examples of building, of art, and of ways of living during Roman times in North Africa have been disclosed, all supported by the agriculture of the Granary of Rome.

But today this great center of power and culture of the Roman Empire is desolation. It is represented by a modern village of only a few hundred inhabitants who live in squalid structures, the walls of which are for the most part built of stone quarried from the ruins of the ancient city. Water erosion has cut a gully down into the land and exposed an ancient aqueduct that supplied water to the city of Timgad from a great spring some 3 miles away.

[FIGURE l0. Ruins of the amphitheater at the former city of Thysdrus, in Tunisia, which would seat 60,000 people. Today, only a few thousand people inhabit this area. The small flock of sheep in the foreground are a fair indication of the land's ability to support life.]

Within and surrounding Timgad, we studied remarkable ruins of great olive presses where today there is not a single olive tree within the circle of the horizon.

On the plain of Tunisia we came upon in El Jem the ruins of a great amphitheater, second only in size to that of Rome. (fig. 10). It was built to seat some 60,000 people, but it would be difficult to find 5,000 persons today Within this district. The ancient city now lies buried around the amphitheater and a sordid modern village is built on the buried city.

What was the cause of the decadence of North Africa and the decline of its population? Some students have suggested that the climate changed and became drier, forcing people to abandon their remarkable cities and works. But Gsell, the renowned geologist who studied this problem for 40 years, challenged the conclusion that the climate has changed in any important way since Roman times.

So Director Hodet of the Archaeological Excavations at Timgad decided as an experiment to Plant olive trees on an unexcavated part of the city where there would be no possibility of subirrigation. He planted young olive trees in the manner prescribed in Roman literature, watering them in the following two long dry summer seasons. These olive trees are thriving, indicating that where soils are still in place, olive trees will grow today probably very much as they did in Roman times.

On the plains about Sfax, ruins of olive presses were found by early travelers, but no olive trees. Forty years ago an experiment to Plant olive trees there was decided upon. Now more than 150,000 acres are planted to olive trees; their products support thriving industries in the modern city of Sfax. These plantings indicate that the climate of today has not become significantly drier since Roman times.

Other students of this baffling problem have suggested that pulsations of climate with intervening dry periods, sufficient to blot out the civilization of North Africa, have taken place. Such undoubtedly could have been the case. But at Sousse we found telling evidence on this point in an olive grove that has survived since Roman times. These olive trees were at least 1,500 years old, we were informed.

I was interested in the way these trees were planted - in basins bordered by banks of earth with ways of leading in unabsorbed storm runoff from higher ground. We passed along this area at a time of heavy rains which showed just how this method had worked since the trees were first planted. If there have been pulsations of climate since Roman times, this grove should show that the drier periods were not sufficiently severe to kill the olive trees. We conclude that it does not seem probable that either a progressive change of climate or pulsations of climate account for the decadence of North Africa. We must seek other causes.

On hillsides between Constantine and Timgad, we found on the land a record that indicates what has happened to soils of the granary of ancient Rome. We found some hills that, according to the botanists, were covered with savannah vegetation of scatted trees and grass. Vegetation had conserved a layer of soil on these hills for unknown ages.

With the coming of a grazing culture, brought in by invading nomads of Arabia, erosion was unleashed by overgrazing of the hills. We can see here on the landscape how the soil mantle was washed off the upper slopes to bedrock. Accelerated runoff from the bared rock cut gullies into the upper edge of the soil mantle, working it downhill as if a great rug were being pulled off the hills.

The accumulation of torrential flows during winter storms is cutting great gullies through the alluvial plains just as it does in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah of our own country. The effect of this is to lower the water table, bringing about the effects of desiccation without reduction in rainfall.

In this manner has the country been seriously damaged, and its capacity to support a population much reduced. Unleashed and uncontrolled soil erosion is sufficient to undermine a civilization, as we found in North China and as seems to be true in North Africa as well.

We traveled across North Africa southward toward the Sahara Desert into zones of less and less rainfall. Beyond the cultivated area in Roman times was a zone devoted to stockraising on a large scale. Thousands of cisterns were built in Roman or pre-Roman times to catch storm runoff from the land to store it for outlying villages and for watering herds of livestock during the dry summer seasons.

Many of these cisterns were being cleaned out and repaired by the French Government before World War II, to be used for the same purpose as they were in ancient times. One of the modern cisterns was four times as large as any Roman cistern, with a capacity of 100,000 cubic feet. This cistern was filled in 2 years and now furnishes water for the seminomads who inhabit this Part of North Africa.

Still farther toward the desert, about 70 miles south of Tebessa, we found a remarkable example of ancient measures for the conservation of water. At some time in the Roman or Possibly pre-Roman period, peoples of this region built check dams to divert storm water around slopes into canals to spread it upon a remarkable series of bench terraces.

This area of unusual interest raises a number of questions we are not yet able to answer. If these terraces were cultivated to crops in times past, they are the best evidence we have that climate has become drier since they were first built. But if they were built for spreading water to increase forage production for grazing herds, as the French are using them today, they are not evidence of an adverse change of climate. This evidence alone could leave us in doubt, but other evidence indicates that water spreading was most used here for crops.

It would be interesting to know the date and the reason for building these terraces. They may indicate that with Roman occupation of North Africa the native tribes were driven beyond the border of the Roman Empire and were forced to devise these refined measures for conservation and use of water in a dry area. Or they may indicate that North Africa was so densely populated that it was necessary to use these refinements in the conservation of water to support the population on the margins of a crowded region.

While the land of North Africa has been seriously damaged, as one can see written on landscape after landscape, the country is still capable of far greater than its present production. In Roman times a high degree of conservation of soils and waters was reached with an intensive culture of orchards and vineyards on the slopes and intensive grain growing in the valleys.

All this depended on efficient conservation and use of the rainfall. We find numerous references to such practices in the literature of the time. But, as nomads swept in out of the desert, their extensive and exploitive grazing culture replaced these highly refined measures of land use and let them fall into disuse and ruin. Erosion was unleashed on its destructive course, and the capacity of the land to support people was seriously reduced.

The veteran student of North Africa, Professor Gautier, answered my query as to whether climate of North Africa had changed since Roman times, in the following way: "We have no evidence to indicate that the climate has changed in an important degree since Roman times, but the people have changed."

We conclude that the decline of North Africa is due to a change in a people and more especially to a change in culture and methods of use of land that replaced a highly developed and intensive agriculture and that allowed erosion to waste away the land and to change the regime of waters.

The westward course of civilization has left its marks in Italy. We found at Paestum, south of Naples, one of the best preserved Greek temples, located on the coastal plain near the sea. Here, there was no overwash of erosional material or accumulation of dust from wind erosion and no gully erosion in the plain. We walked on the same level as the Greeks who built the temple 2,600 years ago.

But population pressure in Italy, under its smiling climate and blue skies, has pushed the cultivation line up the slopes and caused the building of villages on picturesque ridge points. In Italy there are 826 persons per square mile of cultivated land, while in the United States there are only 208.

This method of comparing population density gives us the advantage because of our vast grazing lands that support great herds of livestock. But if we had the same density of population per square mile of cultivated land in the United States as has Italy, we should have 520 million people. This gives us some idea of the relative densities and pressures of population upon the land and accounts for the intensive use not only of the plains but of the steep slopes.

We do not have space to tell the details of how the Pontine Marshes, that for 2,000 years defied the reclamation efforts of former rulers of Italy, were successfully reclaimed recently. This former pestilential area has been drained and rid of malaria and is now divided into farms equipped with reinforced concrete houses of attractive design, where families are established free from perils of malaria and safe in the security of their land.

In southeastern France we found the same condition of intensive use of land on valley floors and on steep, terraced slopes. In the French Alps, population pressure on land of the plains has pushed the cultivation line up the slopes into mountains and has denuded grassy meadows by overgrazing.

This excessive use of the mountainous areas in the French Alps unleased torrential floods that for more than a century ravaged productive Alpine valleys. Erosional debris was swept down by recurring torrential floods' to bury fields, orchards, and villages; to cut lines of communication; and to kill inhabitants of the valleys.

[Figure 11. A terraced citrus orchard in southern France. It is believed that terraces of this type were first built in France by the Phoenicians about 2,500 years ago. Modern French farmers are still maintaining and farming such hillsides, however, because of the scarcity of good land.]

So serious became this menace to the welfare of the region that the French Government, after much study and legislation, undertook in 1882 a constructive program of torrent control. Since that time hundreds of millions of francs have been spent for works of torrent control that are remarkably successful.

We found slopes in southern France cultivated on gradients up to 100 percent with terrace walls as high as the benches were wide. Some of these terraced fields had been under cultivation for more than a thousand years - likely much longer, for the Phoenicians are believed to be responsible for terracing in this part of France (fig. 11).

When the soils of these terraces become fatigued, as the French say, they are turned over to a depth of more than 3 feet once in 15 to 30 years as the need may be. Thereafter, a cover crop is planted on the newly exposed soil material for two or more years, followed by plantings of orchard trees or vines or vegetables.

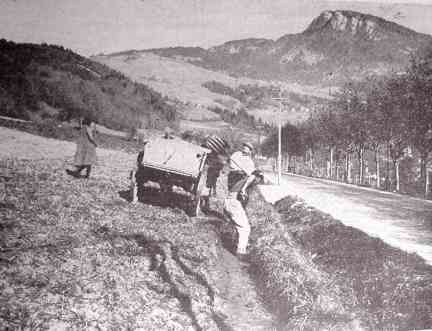

In eastern France we found in various stages adjustments of farming to slopes. In places, terraces were built with rock walls on the contour to reduce slope gradients; elsewhere, rock walls were built on the contour to form level benches. At other places, farmers dug up the soil of the bottom furrow of their fields that were laid out in contour strip crops, loaded the soil into carts, hauled it to upper edges of the fields, and dumped it along the upper contour furrows to compensate for downslope movement of soil under the action of plowing and the wash of rain (fig. 12). This was done each year. Where the slope was too steep to haul the soil uphill, they loaded the soil of the bottom furrow in baskets and carried it on their backs to the upper edges of the field. In this way these farmers of France take care of their soil from generation to generation.

[FIGURE 12. These French farmers are digging up the soil along the lower furrow of their field and loading it into a cart. It will be hauled uphill and spread along the upper edge. They do this job each winter to help compensate for the downhill movement of soil by erosion.]

In southwestern France, in the region of Les Landes, we studied, probably, the greatest achievement of mankind in the reclamation of sand dunes. It is recorded that the Vandals in A.D. 407 swept through France and destroyed the settlements of the people who in times past had tapped pine trees of the Les Landes region and supplied resin to Rome. Vandal hordes razed the villages, dispersed the population, and set fire to the forests destroying the cover of a vast sandy area. Prevailing winds from the west began the movement of sand. In time, moving sand dunes covered an area of more than 400,000 acres that in turn created 2 1/4 million acres of marshland.

Sand dunes in their eastward march covered farms and villages and dammed streams, causing marshes to form behind them. Malaria followed and practically depopulated the once well-peopled and productive region. These conditions caused not only disease and death, but impoverishment of the people as well.

In 1778 Villers was appointed by the French Government to create a military port at Arcachon. He reported that it was first necessary to conquer the movement of the sand dunes, and presented the principle of "dune fixation." About 20 years later Nepoleon appointed his famous engineer, Bremontier, to control these dunes.

Space will not permit my telling the fascinating details of this remarkable story of how the dunes were conquered by establishing a littoral dune and reforesting the sand behind, and how marshy lands were drained by Chambrelent after a long period of experimentation and persuasion of public officials. Now this entire region is one vast forest supporting thriving timber and resin industries and numerous health resorts.

[Figure 13. One of the uncontrolled sand dunes in the Les Landes forest of southwestern France. French engineers have, in the past, brought about 400,000 acres of such dunes under control, and the area is again producing timber.]

Fortunately for comparison, one dune on private land was for some reason left uncontrolled. This dune is 2 miles long, 1/2 mile wide, and 300 feet high (fig. 13). It is now moving landward, covering the forest at the rate of about 65 feet a year. As I stood on this dune and saw in all directions an undulating evergreen forest to the horizon, I began to appreciate the magnitude of the achievement of converting the giant sand-dune and marshland into profitable forests and health resorts.

In Holland we found another of mankind's great achievements - the reclamation of the ocean floor for farming.

Holland is a land of about 8 1/4 million acres, divided into two almost equal parts - above and below high tied level. It is inhabited by 8 million industrious people. Its land included the great delta of the North Sea built up with the products of erosion sculptured out of the lands of Germany and Switzerland and northeastern France, brought down by the Rhine and Meuse Rivers. Now 45 percent of the area lies below high tide level and one-fourth lies below mean sea level. The Dutch from time immemorial have been carrying on an unending battle with the sea. They have become expert in filching land from the grasp of the angry waters of the North Sea.

If the United States were as densely populated per square mile of cultivated land as Holland, the population of the United States would be 1 1/4 billion. The density of population of Holland has called for an increase of its land area.

Rather than to seek additional land by conquest of its neighbors it has turned to the conquest of the sea.

The Zuider-Zee project, two centuries in the planning, is Holland's masterpiece in a 2,000-vear battle with the North Sea. This project adds more than 550,000 acres of new land to Holland's territory, converting the old salt Zuider-Zee into a sweet-water lake renamed the Yssel Meer.

[Figure 14. A Dutch farm in the Wieringermeer Polder of the Netherlands. Only 7 years before this picture was taken this land was covered by the North Sea.]

The Dutch have built great dikes to dam off the sea and have pumped the water out of the basins with great pumping plants. They have diked off the sea and dewatered the land, leached it of its salt, and converted it into productive farm land. We stood on fertile farm land that was the floor of the sea only 7 years earlier, but now is divided into farms equipped with fine houses and great barns (fig. 14). At a cost of about $200 an acre, this land was reclaimed from the sea and divided into farms.

The Dutch by this means have created a new agricultural paradise into which only select farmers may enter. Out of 30 applications for each farm, one applicant is selected on the basis of character, the past record of his family, and his freedom from debt. The successful applicant is put on probation for a period of 6 years. If he farms the land in accordance with the best interests of the land and of the country, he will be permitted to continue for another period. If he fails to do so, he must get off and give another farmer applicant a chance.

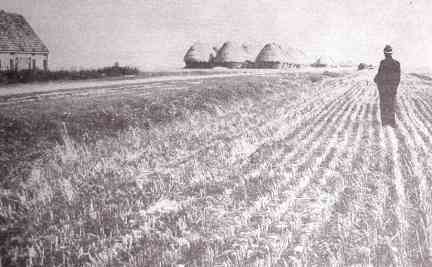

In the mild climate of England, we find that tillers of soil have had little difficulty with soil erosion. This is true because rains come as mists, slopes are gentle, and fields are usually farmed to close-growing crops. England is well suited to grassland farming and to the growing of small grains. Clean-tilled crops have never been in general use. We found fields in England that have been cultivated for more than a thousand years where the yields of wheat have been raised to averages of 40 to 60 bushels per acre. The maximum yield thus far is 96 bushels to the acre. The principal problems before the farmers of England are rotations, seed selection and farm implements.

World War II made new demands on the lands of England. Before blockading action by the enemy, the British Isles depended on imports for two-thirds of their total food supply. One-third of their population was fed from their own lands, requiring about 12 million acres of cultivated land for this purpose. Fully 50 percent more land was plowed to grow food crops. Pastureland and grassland on slopes were cultivated. Soil erosion may become a problem more serious than ever before in British agriculture, because of the extraordinary demands for the growing of food.

And now we cross the Atlantic to the new land which was isolated from the peoples of the Old World until civilization had advanced through fully 6,000 years.

The peoples found here, presumably descendants of tribes coming from Asia in the distant past, had been handicapped in the development of agriculture by lack of animals suitable for domestication and by ignorance of the wheel and use of iron. They had, however, learned to conserve soil and water in a notable way, especially in the terrace agriculture of Peru and Central America and in the Hopi country of southwestern United States. Some have held that this knowledge was brought across the South Pacific by way of islands, on many of which such practices are still found. In any case, lacking iron or even bronze tools, these peoples for the most part still depended largely on hunting, fishing, and gathering - along with shifting cultivation - for their livelihood. Thus, the soil resources seem to have been for the most part almost unimpaired.

To the peoples of the Old World, the Americas were a land of promise and a release from the oppressions, economic and political, brought on by congested populations and failures of people to find adjustments to their long-used land.

North America, as the first colonists entered it, was a vast area of good land, more bountiful in raw materials than ever was vouchsafed any people. Its soils were fat with accumulated fertility of the ages; its mountains were full of minerals and forests; its clear rivers were teeming with fish. All these were abundant - soil productivity, raw materials, and power for a remarkable new civilization.

Here was the last frontier; for there are no more new continents to discover, to explore, and to exploit. If we are to discover a way of establishing an enduring civilization we must do it here; this is our last stand. We have not yet fully discovered this way; we are searching for the way and the light. Here is a challenge of the ages to old and young alike. Here is a chance to solve this age-old problem of establishing an enduring civilization - of finding an adjustment of a people to its land resources.

Our land is like a great farm with fields suited to the growing of cotton, corn, and other crops and with land for pastures, woods, and general farming. In the West, our country has vast grazing lands well suited to the raising of herds of sheep and cattle and fertile alluvial valleys in the arid regions, overawed by high mountains that condense the waters out of moisture-laden winds to irrigate garden lands. Such is the American farm, capable of feeding at least 350 million people when the land is intensively cultivated under full conservation and fully occupied with a complex division of labor that will give us a higher general standard of living than we enjoy today.

But now let us read the record of our own land in a short period of 300 years.

In the past 150 years, our occupation of this fabulous land has coincided with the coming of the age of science and power-driven machines.

Along the Atlantic coast in the Piedmont we find charming landscapes of fields with red soils and glowing grain fields. But in their midst we find an insidious enemy devouring the land - stealing it away, ere we are aware, by sheet erosion, rain by rain, washing it down into the streams and out to the sea. Sheet erosion, marked by shallow but numberless rills in our fields, is blotted out by each plowing.

We forget what is happening to the good earth until we measure these soil and water losses. More than 300 million acres out of our 400-odd million acres of Farm fields are now eroding faster than soil is being formed. That means destruction of the land if erosion is not controlled.

We are not guessing . Erosion experiment stations located throughout the country have given us accurate answers. Let us compare rates of erosion under different conditions of land coverage and use. Measurements through 5 years at the Statesville, N. C., erosion experiment station show that, on an 8-percent slope, land in fallow without cropping lost each year an average of 29 percent of rainfall in immediate runoff and 64 tons of soil per acre in wash-off of soil.

This means that in 18 years, 7 inches of soil (the average depth of topsoil would be washed away. Under continuous cropping to cotton, as was once the general practice in this region, the land lost each year an average l0 percent of rainfall and 22 tons of soil per acre per year.

At this rate it would take 44 years to erode away 7 inches of soil. Rotations reduced, but did not stop, erosion for the land lost 9 percent of the rain and enough soil so that it would take 109 years to erode away 7 inches of soil. That is a very short time in the life of our Nation. But where the land was kept in grass, it lost less than 1 percent of rain and so little soil that it would take 96,000 years to wash away 7 inches of soil. This rate is certainly no faster than soil is formed.

Under the natural cover of woods, burned over annually, as has unfortunately been the custom in southern woods, each year the land lost 3 1/2 percent of rain and 0.06 ton of soil per acre so that it would take 1,800 years to erode away 7 inches of soil. But where fire was kept out of the woods and forest litter accumulated on the forest floor, the land lost less than one-third of l percent of the rainfall. And, according to the calculations, it would require more than 500,000 years to wash away 7 inches of soil. Such a rate of erosion is indeed far below the rate of soil formation.

Here in a nutshell, so to speak, we have the underlying hazard of civilization. By clearing and cultivating sloping lands - for most of our lands are more or less sloping - we expose soils to accelerated erosion by water or by wind and sometimes by both water and wind.

In doing this we enter upon a regime of self-destructive agriculture. The direful results of this suicidal agriculture have in the past been escaped by migration to new land or, where this was not feasible, by terracing slopes with rock walls as was done in ancient Phoenicia, Peru, and China.

Escape to new land is no longer a way out. We are brought face to face today with the necessity of finding out how to establish permanent agriculture on our farms under cultivation before they are damaged beyond reclamation, and before the food supply of a growing population becomes deficient.

In an underpopulated land such as ours, farmed extensively rather than intensively, there will be considerable slack before privations on a national scale overtake us. But privations of individual farm families, resulting from wastage of soil by erosion, are indicators of what will come to the Nation. As our population increases farm production will go down from depletion of soil resources unless measures of soil conservation are put into effect throughout the land.

We must be in possession of a certain amount of abundance to be provident: a starving farmer will eat his seed grain; you will do it and I will do it, even though we know it will be fatal to next years crop. Now is the time, while we still have much good land capable of restoration to full or greater productivity, to carry through a full program of soil and water conservation. Such is necessary for building here a civilization that will not fall as have others whose ruins we have studied in this bulletin.

A solution to the problem of farming sloping lands must be found if we are to establish an enduring agriculture in the United States. We have only about 100 million acres of flat alluvial land where the erosion hazard is negligible, out of 460 million acres of land suitable for crops. Most of our production comes from sloping lands where the hazard of soil erosion is ever present. This calls urgently for the discovery, adaptation, and application of measures for conserving our soils.

In the results of the Statesville erosion experiment station we saw how a forest with its ground litter was effective in keeping down the rate of soil erosion well within rates of soil formation. Out of untold ages of unending reactions between forces of erosion that wear down the land and forces of plant growth that build up the land through vegetation, the layer of forest litter has proved to be the most effective natural agent in reducing surface wash of soil to a minimum. Here is clearly our objective for a permanent agriculture, namely, to safeguard the physical body of the soil resource and to keep down erosion wastage under cultivation as nearly as possible to this geologic norm of erosion under natural vegetation.

A few years ago I came upon a hill farmer in an obscure part of the mountains of Georgia, He was trying to apply on his cornfield the function of forest litter as he saw it under the nearby forest on the same slope and same type of soil.

It was for me a great experience to talk with J. Mack Gowder of Hall County, Ga., about the fields he had cultivated for 20 years in a way that has caught the imagination of thoughtful agriculturists of the Nation. We talked about the simple device of forest ground litter and how effective it is in preventing soil erosion even on steep slopes, and how he thought that if litter at the ground surface would work in the forest it ought also to work on his cultivated fields along the same slope.