FOOD vs. POPULATION...

FOOD vs. POPULATION... FOOD vs. POPULATION...

FOOD vs. POPULATION...From Chapter One, The QUANTITY CRISIS: The Land of Plenty? of "World Crisis in Agriculture" booklet by the Ambassador Agricultural Research Dept. 1974 including: Dale Schurter MS, Chairman, Allen Stout D.V.M., Paul Syltie PHD, Dave Swaim MS, Neal Kinsey, consultant, Zoell Colburn, consultant, Loren Weinbrenner, off. mgr., Dave Leach, farm mgr., Dean Klepfer, assist. mgr.

America -- the land of plenty, breadbasket of the world!

For nearly 200 years American food stocks have comfortably fed America's people, often with enough left over to help less fortunate nations. Despite man-made or weather-caused shortages, no American generation has suffered through the pangs of massive famine, such as Biafra, India, sub-Saharan Africa and Bangladesh have recently experienced. Food shortages, when they occurred, have been local and temporary in America.

To American eyes, such food shortages seem to occur only in lands where gaunt oxen pull knotty wooden plows through mud-slogged soils, or where gnarled hands eke out a bare existence upon yellow, eroded soils amid squalid huts. To most Americans, all such pain is safely segregated -- south of the border or far across the ocean.

America's Food Chain

Could such famines ever strike in prosperous, abundant, vibrant America? Take a look at the average American farmer. Though his productivity is enviable by world standards, a closer look reveals that the American farmer could easily suffer the same fate as his Asian counterpart. By scrutinizing the average American farmer and his dilemma, we can see seven interdependent potential problems of crop production:

These seven factors, listed in chronological order from land to larder, comprise a food chain. Complete failure of any one link, or partial failure of several links in the chain, could bring catastrophic food shortages.

I. No More Land

There is no unexplored "El Dorado" left for mankind to farm. America, long the breadbasket for some "have-not" nations, is now becoming more concerned with feeding itself. Lester R. Brown, a leading American agriculturist, recently stated that at least half of America's 50 million acres of reserve cropland would have to be put back into production. In 1974 it was. However, most of this remaining cropland is so marginal that erosion and fertilizer shortages canceled out most of the expected gains.

"For the first time since the end of World War II," he added, "the world is without either of the two important safety valves in the world food economy -- surplus stocks of grain and a large reserve of United States cropland that could readily be brought back into production."

New acreage is only half the problem. The declining quantity and quality of current acreage is even more serious. An estimated 400,000 productive farm acres are lost each year in the United States due to erosion. Millions of other acres are partially lost due to wind and water erosion.

In addition, over a million acres of United States land -- much of it prime agricultural farmland -- are lost each year to highways, housing additions, shopping centers, and other suburban developments. According to one exhaustive computer study, entitled "The Limits to Growth," nearly half of all arable land available for agriculture will be consumed by urban-industrial growth before the year 2050. Meanwhile, population will quadruple!

II. Genetic Vulnerability

Another potential problem within agriculture's "quantity crisis" involves the type of seed used. As the June 1971 Scientific American warned: "Hardy high-yield varieties of major food crops, carefully crossbred and highly selected, are the success story of modern plant genetics, but they may carry the seed of their own destruction."

These seeds, when sown by machine, must be uniform in size and shape, and the fruit, to be reaped by machine, must be uniform in size and shape, too. The seeds or fruit must also ripen at the same time to be harvested economically.

For this reason, most major food producers utilize only a very few seed varieties per crop. Two genetic pea types, for instance, account for 96 percent of the entire pea crop in the United States. Using only one or two seed types, however, increases vulnerability to decimation by just one virus, fungus, or other disease.

For example, consider the corn blight that diminished the U.S. corn crop by about 700 million bushels during the summer and fall of 1970. The disease, a fungus which attacks both the leaves and the grain of corn, affected plants with a "T-cytoplasm" genetic strain, which included 90 percent of all hybrid corn grown in the United States.

This vulnerability to disease stems from the very narrow base of genetic uniformity which aids the efficiency of agribusiness, but opens the crop up to widespread pathogenic disease.

III. Declining Soil Fertility

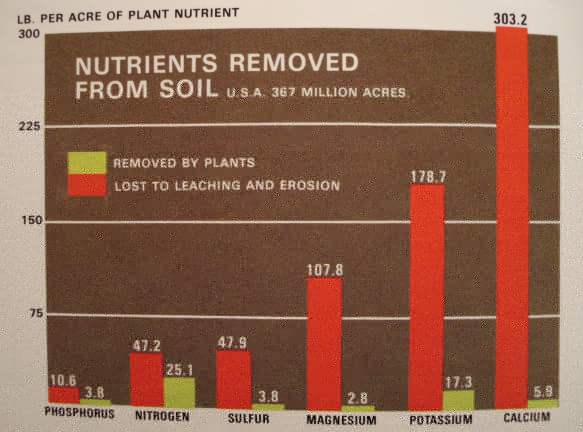

The life-saving topsoil of our planet averages only seven inches in depth -- equivalent to an invisible film three-millionth of an inch thick on a desk globe -- yet nearly all the matter constituting our food, clothing, and shelter comes from it. Four billion humans depend on this thin layer for life. How long can the world's productive topsoil withstand the combined onslaught of erosion, improper fertilization, and over-farming?

Graph - NUTRIENTS REMOVED FROM THE SOIL U.S.A. 367 MILLION ACRES.

Graph - NUTRIENTS REMOVED FROM THE SOIL U.S.A. 367 MILLION ACRES.

The extent of soil erosion in America is massive, but the loss of soil nutrients by erosion is even worse than the volume of erosion would indicate. In New Jersey, for instance, soil materials removed from test plots by the selective action of erosion contained 4.7 times as much organic matter, three times as much phosphorus, and 1.4 times as much potassium as the original soil in the plots. Erosion takes the prime ingredients of soil and leaves the dross behind.

Another sign of declining soil fertility is the advent of artificial fertilizers. Chemical fertilizer is the "fuel that has powered the Green Revolution," according to 1970 Nobel Peace Prize winner Norman A. Borlaug. In order to feed the new hybrid crops of corn, wheat, sorghum and rice constituting the "green revolution," it is absolutely essential to churn out more and more tons of chemical fertilizers.

Unfortunately, great quantities of natural gas, electrical energy, and other energy forms needed to produce these fertilizers are in short supply and are ultimately nonrenewable, which takes us to the next link in the food chain.

IV. Energy Crisis on the Farm

While the number of American farmers has been cut in half this century, the average acreage of each farm has more than doubled, from 150 acres to 380. To face the challenge of "produce more or perish," farmers have become almost entirely dependent for their survival on machines and the energy sources which run these machines.

In 1850, fuel sources on the farm were 95 percent naturally renewable (men, animals, wind, water, and wood), while today 95 percent of energy sources used are nonrenewable (coal, oil and natural gas). Not only are many of the products of the latter forms of energy harmful to the environment, scarce and expensive, they also can never be retrieved or renewed. Shortages of these fuels are therefore inevitable.

A farmer depends on a heavy supply of fuel at certain times of the year, rather than a constant steady small supple, such as urban homeowners and automobile drivers need. In the spring of 1973, however, as planting was in full swing, fuel was often unavailable. Cotton crops just sprouting could not be tended; preparation and planting on some farms was halted. Longtime fuel customers waited precious days for delivery of their fuel.

Prevention of similar or worse fuel crises appears to be impossible. A cold winter with excessive drains on fuel reserves, a Middle East confrontation, or organized labor disputes within the oil industry could jam the brakes on vital sectors of agriculture again.

Attorney General William Saxbe noted the irony of America's upside-down priorities when he said: "I think when farmers can't get enough gas to harvest their crops at the same time thousands of persons are burning up gas in recreational pursuits, rationing is very possible."

V. Manpower Problems

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz has stated that more young, progressive, and educated blood needs to be injected into the life veins of agribusiness. Yet the average farm operator is 55, and his 20-year-old sons and daughters are rapidly heading for the cities, for economic as well as personal reasons.

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz has stated that more young, progressive, and educated blood needs to be injected into the life veins of agribusiness. Yet the average farm operator is 55, and his 20-year-old sons and daughters are rapidly heading for the cities, for economic as well as personal reasons.

First look at the economic factors. The average beginning farmer needs the highest outlay of capital among all United States businesses, including steel manufacturing. A young farmer needs in excess of $200,000 to set up an average 400-acre corn and poultry farm in Nebraska. Many farm youth are turned off at the prospect of eternally being in debt (more on this economic crisis in chapter three).

Besides the cold, hard economics of farming, personal reasons also drive youths from the farm -- the modern ideal of "pleasure before work" has gripped a large share of younger America. A hard day's work under the sun is spurned in favor of a higher-paying desk job. High-paying jobs are in the cities, while most farmers are unable to pay an equivalent wage.

Another major labor problem is the recent trend toward unionization of farm labor. No longer is the "family farm" the only primary production unit. Corporations run many of the largest farms, and large corporations usually engender large labor unions. Both sides demand justice, and the consumer is caught in the middle.

Should an organized farmer's union ever gain widespread membership, it is feasible that a strike -- a food holdout -- could rapidly deplete supermarket shelves and storage bins. In 1973, National Farmer's Organization livestock and milk "holding actions" (strikes) were a small premonition of more disruptive food strikes in the future.

VI. Unpredictable Weather

Every link in the food chain discussed so far is extremely important, but one factor stands out above all others. No other factor can spell famine faster than bad weather; yet this one factor is mostly out of man's control.

The most important aspect of weather is precipitation. In 1972, for instance, Russia was hit by insufficient snow cover which caused much of its winter wheat to freeze out. Then late spring rains delayed planting, followed by a summer drought which decimated that late planting. Later, autumn rains came which impaired harvest, resulting in their worst wheat crop in 100 years.

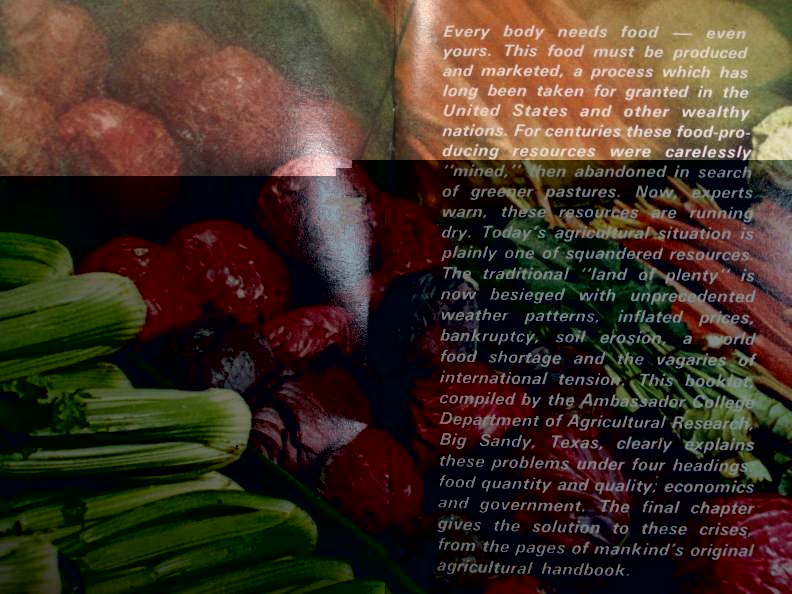

(Photo caption) Island Farms, shown here during the April 1969 floods near Fargo, North Dakota, were also a common sight during the spring of 1974 in the U.S. Midwest.

(Photo caption) Island Farms, shown here during the April 1969 floods near Fargo, North Dakota, were also a common sight during the spring of 1974 in the U.S. Midwest.

The United States is fortunate in having had many years of favorable weather, or bad weather "saved" in the end by "rain in due season" or a timely thaw. Following the devastating floods of 1973, for instance, skies quickly cleared, fields dried, and farmers in most areas were able to plant their crops. Had the rains continued much longer, farmers would have been in deep trouble.

Some day, those needed rains and breaks in the weather just won't come! Meteorologists don't give us much encouragement. Prolonged dryness in some areas (and excessive rain followed by drought and hot winds in others) inflicted heavy losses on 1974 crops. Yet few people in today's air-conditioned society truly worry about weather.

How much odd weather is caused by man's intrusions into the environment? Experts are still debating this, but one cost to agriculture is sure: the "ill winds" of air pollution reap at least $500 million in crop loss annually.

VII. Food Storage and Distribution

Very little food is eaten as soon as it is harvested. Most food travels hundreds of miles and many days before it is consumed. In order for man's fragile food chain to survive, harvested crops must be kept safe from wasteful rots, fungi, insects, and animals. How has this battle been faring?

In the world at large, not very well! The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) termed storage losses as "enormous." Nobel Prize winner Sir Robert Robinson estimated storage losses as between 15% (average in the U.S.) and 35% (in underdeveloped nations) lost to pests or diseases.

Even in the United States, a possible energy shortage could mean losses of refrigerated meats and vegetables. Severe weather problems could impair storage and distribution, and a labor strike would also hold up the vital links of distribution. As with all links in the food chain, distribution is subject to the whims of fuel shortages, snowstorms, floods, internal political crises, and simple oversights, such as a "boxcar shortage" which has struck the United States railroads in recent years.

Alert to these dangers, many farmers have bought their own grain bins, storing as much of their own produce as possible. Wheat farmers, fearing they may get burned again by artificially low prices or a "wheat deal" with a foreign nation, are prepared for the next time. But is the consumer prepared?

Another Quantity Crisis (population)

The seven links in the food chain, described above, show just how vulnerable, how fragile, how "finely tuned" our ultra-technological, highly sophisticated and inter-dependent economy is. Never before in man's history has so much food depended on so few food producers. It is truly man's greatest gamble!

While modern-day agronomists diligently treat half of the problem -- food quantity -- the "other" quantity crisis continues apace: runaway population. With 70 million new mouths to feed each year, no nutritional equation can ignore the sheer volume of humankind to feed. As Dr. Paul Ehrlich said: "Whatever you cause, it's a lost cause without population control." Such control is not a panacea, but it is a necessary beginning step.

The vast majority of the world currently suffers from both crises of quantity: not enough food and too many people. Each year, five million people starve to death, and each night half the world goes to bed (and wakes up!) hungry. But this, Americans think, is a crisis that will never attack their own families.

This chapter has shown you otherwise. America's food economy is dangerously fragile for the following reasons:

1) The quantity of food produced is often beyond man's control. Various external factors, such as disease or weather, affect the food chain and can easily upset it.

2) The food production chain is integrally linked to the remainder of the economy. If the economy fails, so will food production and distribution, as in the Depression of the 1930's.

3) Each of the seven vital links in the food chain is integrally linked to the others. A break in one link, or a wearing of many links, would severely affect the entire food chain.

So far, America and the West have been spared, but is time running out within "the land of plenty"?

Editors note: Since this was written in 1974, each of these areas have become even more vulnerable and increasingly depleted. Today America continues to import more and more of its foods...

Last Update: 10/27/07